Scientists found that day-to-day well-being does not reflect how well things are going, but whether things are going better than expected.

The subjective well-being or happiness of individuals is an important metric for societies and a common question in the social science of well-being asks “How happy do you feel on a scale of 0 to 10?”

Responses are often related to life circumstances and population demographics including wealth but we know little about how the cumulative influence of daily life events are aggregated into subjective feelings. Until now.

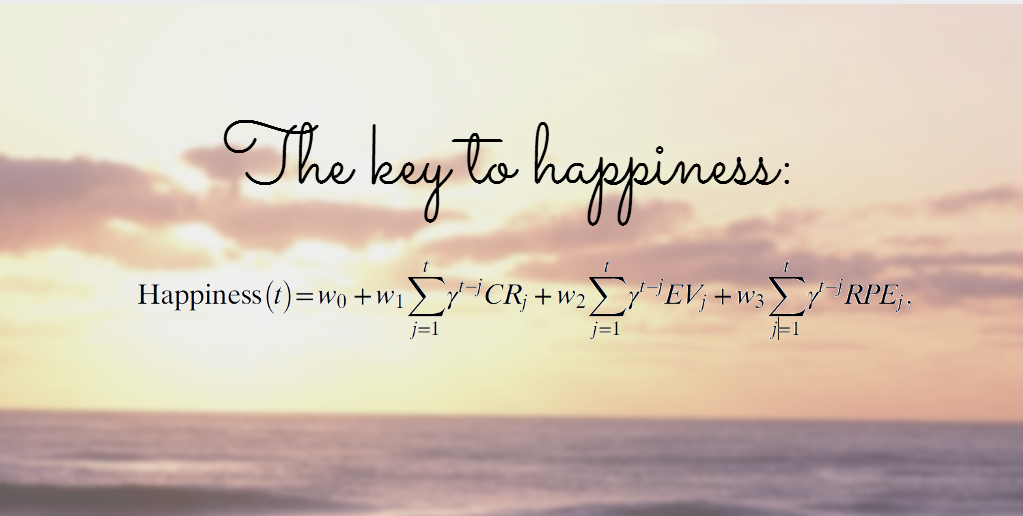

A team of researchers at the University College London, led by Dr. Robb Rutledge, have developed a mathematical equation to assess happiness.

Their project started with 26 people who were repeatedly asked how happy they were during a decision-making task where the choices were linked to monetary gains or losses. Their brain responses were constantly monitored with a functional MRI. Later, this method was involving over 18,000 participants from all around the world using a smartphone app called “The Great Brain Experiment” in which self-reported happiness was related to recent rewards and expectations.

The scientists found that the equation they had built during the study’s initial decision-making task to predict how happy participants were still worked during the second stage.

Dr. Rutledge was surprised that the study found expectations to have such an important role in determining happiness:

We expected to see that recent rewards would affect moment-to-moment happiness but were surprised to find just how important expectations are in determining happiness. In real-world situations, the rewards associated with life decisions such as starting a new job or getting married are often not realized for a long time, and our results suggest expectations related to these decisions, good and bad, have a big effect on happiness.

He declared that he was surprised to see just how well the equation functions. He explains that your expected outcomes heavily impact your state of mind.

Life is full of expectations — it would be difficult to make good decisions without knowing, for example, which restaurant you like better. It is often said that you will be happier if your expectations are lower. We find that there is some truth to this: lower expectations make it more likely that an outcome will exceed those expectations and have a positive impact on happiness. However, expectations also affect happiness even before we learn the outcome of a decision. If you have plans to meet a friend at your favorite restaurant, those positive expectations may increase your happiness as soon as you make the plan. The new equation captures these different effects of expectations and allows happiness to be predicted based on the combined effects of many past events.

So basically, the secret of happiness is all about lowering your expectations: A good day is when things are going better than expected.

The study was published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: http://www.pnas.org/content/early/2014/07/31/1407535111.abstract